In John McNamara’s work, painting becomes a form of excavation—of memory, of history, and of the image itself. Rather than presenting a straightforward scene or subject, McNamara weaves layers of photography, paint, and narrative suggestion into pieces that ask viewers to look deeper. His art doesn’t shout—it whispers, beckons, and rewards close inspection.

At the heart of his practice lies the use of photography as a hidden element. He integrates images of real people, specific places, and everyday objects—not as central features, but as embedded truths. These glimpses of reality form the quiet backbone of works that stretch beyond personal memory into broader conversations around transcendence, cultural legacy, and shared human experience.

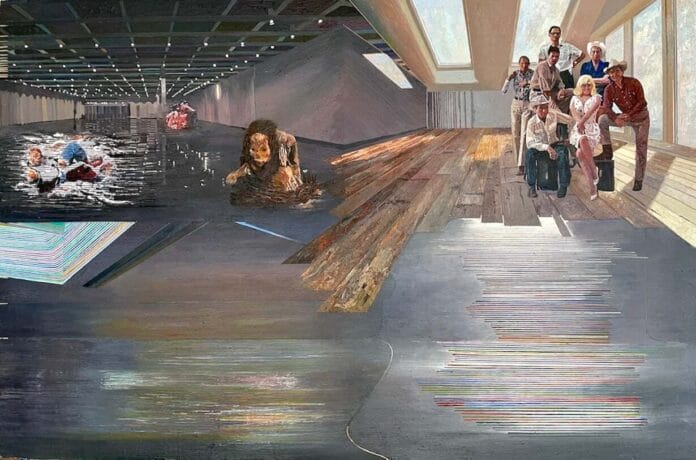

“Misfits”: Bodies, Myths, and the Weight of History

One of McNamara’s most haunting recent works, “Misfits” (Oil on Paper on Panel, 2025), exemplifies this approach. While abstract in its surface presentation, the painting is rooted in the stark, sobering reality of high-altitude death. Inspired by the frozen bodies left behind on the alpine slopes—many of which remain unrecovered due to the danger and cost—McNamara translates this grim phenomenon into a visual elegy.

These bodies, sometimes used as trail markers, are not merely morbid relics; in McNamara’s world, they become metaphors for sacrifice, endurance, and the human desire to reach higher, even at great cost. The painting doesn’t depict them literally. Instead, it channels the cold permanence of snow, the erosion of flesh over time, and the silent passage of climbers into myth.

“Misfits” challenges us to consider how we mark the way for others—not only with triumph, but with failure, fragility, and frozen remnants of our efforts.

Ancient Histories, Sacred Remains

McNamara’s work often draws from ancient cultural histories, invoking long-forgotten rituals, symbols, and truths. In his research for “Misfits,” he explored the story of The Lady with Long Hair, a mummy discovered at Huaca Huallamarca in Lima, Peru. Dating to around 900 AD, she was preserved with over two meters of hair intact, and a seabird tattooed on her body—a powerful symbol of her civilization’s reverence for the ocean.

For McNamara, such archaeological finds are more than scientific marvels—they’re intimate human echoes. These stories are absorbed into his work not as illustrations, but as emotional textures. In “Misfits” and related pieces, you can find symbolic traces: flowing forms like strands of hair, ancient marks embedded in skin-like surfaces, and the suggestion of sacred geography.

Rather than reconstruct these histories, McNamara lets them haunt his compositions. Their presence is subtle, like a memory just beneath the surface—evocative, elusive, and quietly profound.

Pop Culture as Pathos: The Other “Misfits”

The title of McNamara’s painting also references the 1961 film “The Misfits,” a cultural artifact as fraught and layered as any ancient tomb. Starring Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, and Montgomery Clift, and written by Arthur Miller, the film was notorious for the personal demons of its cast. It wasn’t just a story about broken people; it was made by them.

Monroe’s vulnerability, Gable’s exhaustion, Clift’s rawness—all blurred the line between performance and real life. By the time the film was released, it had become more than a movie—it was a requiem for a fading Hollywood era, a mirror held up to the destructive machinery of fame.

In referencing this film, McNamara isn’t just being clever. He’s drawing a line between fame and fragility, between frozen climbers and broken actors, between ancient mummies and modern myths. His “Misfits” are the people history forgets—or remembers for the wrong reasons. They are emotional landmarks, guiding us through treacherous emotional landscapes.

Photography as Ghost: The Invisible Layer

A defining feature of McNamara’s paintings is his use of photography as a hidden foundation. Photographic images are layered beneath oil and paper, often so obscured they’re barely visible. But they’re there—real people, real objects, real places, captured and buried like time capsules.

This approach invites viewers to engage in a kind of visual archaeology. Beneath each surface lies something lived: a body, a moment, a structure, a story. The images become ghosts within the work, lending it a depth that is not purely visual, but emotional and temporal.

In this way, McNamara’s paintings act like palimpsests—surfaces that have been written, erased, and rewritten. Every mark is a trace of something else. Every figure, a remnant of someone once present.

Navigating Loss, Memory, and Transcendence

Through these layered techniques and references, John McNamara’s art engages deeply with the themes of memory, loss, and transcendence. Whether contemplating the final resting places of alpine climbers, the tattoos of ancient women, or the fading light in a Hollywood legend’s eyes, his paintings are meditations on what it means to persist—to leave something behind that matters.

His work is not morbid. It’s reverent. It recognizes the inevitability of loss, but also the beauty of what lingers: stories, symbols, the impact we make on the world and each other.

Conclusion: Markers on the Mountain

John McNamara paints the people and things we might otherwise overlook: the misfits, the forgotten, the lost. Through his distinctive layering of paint and photography, he turns individual stories into universal reflections. His work reminds us that even those frozen in time—whether in snow, celluloid, or stone—still guide our way.

Like the bodies used as markers on the mountain, his subjects are both tragedy and compass. And in revealing them, McNamara invites us to not only look closer, but to carry their stories forward.